Hello everyone, my name is Nicola and I'm one of the curators here at Studio Voltaire. Thank you so much for joining us this evening. I wanted to start by giving a very brief intro and thanks to our speakers this evening. Firstly, I want to thank Tom O'Sullivan — I've written this for Joanne Tatham and Tom O'Sullivan — so I'm adjusting to singular, sadly, as Joanne has become poorly and is unable to join us tonight. But thank you so much Tom, for doing so. Joanne and Tom have been collaborating since '95 and Studio Voltaire has been really privileged to work with them on a number of exhibitions and commissions since the start of 2005. And when we started our capital renovation project, we approached Joanne and Tom with maybe a kind of unusual proposition, which was to create a permanent artwork within our public toilets. The result of that is THE INSTITUTE FOR THE MAGICAL EFFECT OF ACTUALLY GIVING A SHIT (A NOTE TO OUR FUTURE SELF), which opened at the end of last year. And I think it ended up being a really interesting extension of your work and the way that you interrogate the function and status of art in public space. And I think for us at Studio Voltaire it has been a really amazing opportunity to kind of embed some of that commissioning history in our building. Tom is joined by Fiona Jardine, who is a long-term collaborator of Joanne and Tom's. Her own research focuses on authenticity, appropriation and authorship in the visual arts, as well as contemporary critiques of design and craft narratives. And her recent work has included designing a trade union banner for ScotPep, which is a Scottish charity promoting sex worker's rights, as well as exhibitions at Tramway, ICA, London and Glasgow International. So, we might be moving about the building a little bit this evening. Please feel free to get a drink if you don't already have one, or refill when you need to, and I'll pass over to Tom and Fiona. Thank you so much.

Thank you for the introduction. It seems — when you were saying how long we've known each other — it doesn't feel as long, does it?

No, no.

Which is nice.

Yes, and it’s interesting to look back on the projects we have done together. I guess Joanne and I have a core collaboration — which has gone on for something like 25 years — but the three of us have also worked quite regularly together. First thing we did together was in 2005 I think. I find this porous nature of collaboration interesting. How there is a core collaboration and then further collaborations that move outwards from this and are fluid.

Yeah, I mean, I met Joanne before I met Tom. Joanne was my tutor on the MFA in Glasgow and I think that's when I first met her. I remember her tutorial quite well. It was very 'Joanne' in the sense that she was, well, she had such a different approach to the rest of the tutors, who, to my mind, had quite... not a problem with what I was doing, but they didn't understand why I was interested in, for example, still life at the time. I was kind of making still lifes and Joanne took it seriously, but humorously. I think our relationship from then on, including you, has proceeded on that basis. Fundamentally that’s how I met Joanne and it was much later on that we became friends outside of the MFA at Glasgow School of Art — which you both did. You both became friends and we all did the MFA at one point!

Yes, It's a strange experience not having Joanne here. We have occasionally done talks without each other, but I haven't done one for a long time. It’s like Joanne is a kind of ghost presence here. And it's particularly strange because the practice is really born out of a dialogue, a conversation between the two of us. That's the engine of the practice. So I’m afraid all you have here are a few disconnected cogs. I was reflecting about this when Joanne said she couldn’t make it and thinking it could also be a good opportunity to consider the artwork over there, separate from me. I’ve got some thoughts about my role in making it but I’m also interested in how it’s now functioning and what other people think about it. I don’t want to come across as an authority on it. Maybe that will come out in the conversation.

Yeah, and we'll go and visit it. When I first saw the toilet it was on Twitter, so pictures of it, of people taking selfies in it. Wasn't it called 'the most instagrammable toilet in London' or something?

It was.

Yeah. It came through to me in that way, and it looks stunning in the digital images online. So before I saw it physically, I suppose I was thinking a little bit about the aesthetics and also what I know of your aesthetics and the kind of materials that might be used. And I was thinking about a few public toilets that I would link it to. The first one I thought about was a toilet that I visited which had a plaque declaring it to be the best toilet in Scotland. This was a long time ago, so I won't be able to tell you what year it was, but it had a brass plaque saying, 'VOTED BEST TOILET', a bit like a kind of B&B Rosette Award. And there was nothing remarkable about this toilet. It was at Stranraer Ferry Terminal. But I think it had been voted the best because of the cleanliness of it and the care that the people looking after the toilet had taken to make sure that it was a nicer place for people on their way to or from Belfast, for anyone using the toilet on their journey, as a place of repose. And I think that's why it had been voted the best toilet. It was a toilet that had quite a lot of traffic through it, but it was clearly always clean and people were appreciative of that. So I thought about that and I thought about the title of your work, which we'll see is painted on a mirror.

And then, aesthetically, I was thinking about Glasgow's grand 19th century tradition of attention to detail in public spaces and the quality of materials used in some of Glasgow's public spaces, including toilets. And then I was put in mind of the famous Victorian toilet at Rothesay on the west coast of Scotland, at the end of a train line you can get from Glasgow. If you're going to Bute, if you ever go to Mount Stuart, you get the train to Wemyss Bay before crossing to Rothesay on Bute by ferry. It's a very famous toilet. It's beautiful. It's marble and glazed ceramic, it's got glass cisterns. It has been restored and kept in its Victorian glory, but it is designated as a ‘male’ toilet. You can take a tour of the toilet because it's such an architectural high point. I remember going on the tour, and the tour guide, when asked, 'Why is it just the male toilet that we can tour?', said, 'There wasn't the equivalent built for women' and recounted the story that women on their way through Wemyss Bay were just expected to walk along and piss as they were walking: their wool petticoats would absorb the urine and their long frocks would cover the petticoat. Now, I don't know if that is historically accurate and I haven't researched that at all, so I don't know. It's a good story though, and I bought it at the time. It stuck in my mind in relation to this edifice of Victorian engineering and high aesthetics.

So, I was thinking of those two examples in relation to your toilet, as well as having seen it on Instagram. On all those levels, it's an interesting context to work in.

Well, the way it came about was Joanne having a conversation with you, Joe, almost like a joke about doing something in the toilets as part of the redevelopment. There is something about the space of public toilets, which has a kind of awkwardness, or perhaps shame, attached to it. Joanne and I have always been drawn to those kinds of situations, partly because I think we need problematic situations in order to make work. And the more problematic the situation, the more awkward it is, the more it seems to generate something, it seems to pull something out of us. Then we get involved in a process, and then the process takes us somewhere, so the opportunity to do this commission was actually quite a good one for us.

Our starting point was the redevelopment Studio Voltaire was undergoing and getting a sense of what was starting to happen, the kinds of architectural languages that were coming in as part of the Matheson Whitely plan. We became interested in introducing another kind of language that would, in a sense, push up against what was proposed by the architects. This was not explicitly that kind of Victorian grandeur you mentioned in Wemyss Bay. However, when you go and see the toilets, you’ll see one of the starting points was those beautiful hand-dipped tiles that you get on the outside of Victorian pubs and in toilets. Our tiles have been made with the same process, all the glazes are very particularly mixed and each tile that you see has been hand-dipped and then fired. So they've all gone through that same process, which I think gives a particular quality. Shall we go and have a look?

Now’s probably a good point to go and take a look.

I’ll just say a couple of things quickly before we take a look inside the cubicles. First, that this is an artwork. It’s an experience. It’s a sort of stage set. It’s activated when someone goes to the toilet — you enter into the artwork — that’s what’s important to us (the group are standing in the corridor leading to the individual toilets). There are three cubicles, each designed in a particular way, but the work is the whole experience of walking from the café, getting to here, seeing yourself in there (pointing in the mirror), walking up to it and thinking, 'Hmmm, THE INSTITUTE FOR THE MAGICAL EFFECT OF ACTUALLY GIVING A SHIT (A NOTE TO OUR FUTURE SELF)', and then entering one of the cubicles, whichever one you might pick, and then leaving and walking back to the café or wherever. That’s the artwork.

This is the one I saw on Instagram (looking into the end cubicle). It’s interesting to think about which one is ‘most Instagrammable’. But this other one (indicating the adjacent cubicle) the sort of fleshy red one, do you want to tell us about the colours of this?

Well, to begin with the one at the end here — just put your head in — this one is a very, very intense experience. But it’s potluck, which one you go into, whether you get this one with the wow factor or you enter the pinky red one or you might just go into the blue one. You might entirely miss the spectacle in the end one. We were interested in how three different cubicles might make for a more absurd shared experience. Back in the café you might mention to a friend, 'Oh, they’re great toilets' but actually your friend might have gone to the other cubicle and had a different kind of experience.

In terms of how we made this artwork, it began with quite detailed maquettes. Everything is modelled at a tabletop scale and this allows for a particular way of working. You have the maquettes set up in the studio and it gives you the opportunity to imagine visitors walking around within the work. We had a model of this whole wall with the corridor and the three cubicles leading off — it gives you an ability to make the whole situation as one work.

And if you come a bit closer into this one at the end — although it is a kind of spectacle, it was important to us that the surfaces weren’t quite right. That perhaps things weren’t quite working in the way you might expect. The scale of the tiles and the particular palette of the glazes might seem a bit off (entering the end cubicle and looks up and around at the tiled walls). And if you come in even closer you can see how the four walls work together. It’s as if they have just been jammed up against each other, with no sense of the patterns actually going carefully around the walls. As if each wall has been cut out and then simply butted together one, one, one, one (pointing to where the tiles abut each other in the corner of the cubicle). You can see here the details where the pattern connects to the next side, how it leaves awkward thin slithers of tiles at one end, which is not something you would really do if considering an overall design. So the walls appear more like a sequence of surfaces put together for an effect. Then there is the flooring and we had to think about how it might work as another surface in relation to the walls. We spent a long time thinking and testing out what we could do with the flooring. We knew it had to have a sense of being a different kind of language to the walls, that the floor should provoke you to look back at the walls in a different way (returning to the corridor that adjoins the individual toilets). You can come in here later and have a good look if you want. See the details.

We produced the tile patterns as drawings, which were then worked up as CADs. This was quite an involved process, and we became interested in allowing ourselves to follow certain systems that emerged. Allowing the systems to follow through and see how they might interpret the logic of our drawings. So we've got some very strange kinds of moments going on where you might have a tiny tile that doesn't necessarily make sense if you were thinking about this only as a unified tile design. There is a tension how these different systems come together or lie on top one another.

The other significant thing we did, or rather didn’t do, is we didn't pick the actual sanitary ware — the sinks and the toilets. These are the sinks and toilets that Studio Voltaire and Matheson Whiteley were planning to use anyway. We became interested in these choices by the architects and the kinds of design or architectural language they suggested. So we just kept these choices as they were, with the objects sitting on top of the surfaces we were bringing in, allowing them to stand out as ready-mades.

What else can I say? Anybody got any questions? The circular mirror? Yes, that was very much Matheson Whiteley as well. We went with that decision in the two cubicles on the right, but we also thought we’d utilise it, bring it out and replicate the mirror here in the corridor as a device for our title. However, in this toilet (pointing towards the cubicle with the blue and purple tiles) we did make a slight change to the shape of the mirror. Something that might alter your perspective as to the kind of space you were walking into. So you can see, different approaches and strategies were taken but all towards the same goal.

Re-visiting the work now, six months later, I’ve been thinking there’s a kind of a duality to the experience. On the one hand you are put on the spot — ‘I thought I was just going to the loo’ — but then you have the text and yourself reflected in the mirror through the text. There is a confrontation in terms of that classic provocation — ‘What do you represent?’ How are you thinking about this? How are you responding? This is something a lot of the work I make with Joanne does. But then you can go inside the cubicle and you can close the door behind you, lock it, sit on the toilet and you've got a sort of safe space to reflect on all that. And I think that's maybe what the toilets have got, a kind of duality as an artwork, both somewhat confrontational and provocative, but also something joyful and in some senses a safe space or a kind of an imaginative space for you to be in.

And you chose all the other elements? Because I commented when I came into this one on the toilet brush (gesturing towards the entrance to the cubicle with the red and pink tiles). There's some deliberate placing going on, and the colour of it...

That's right, the accessories, fixtures and fittings were considered and chosen by us. Like with the sanitary ware, this was very much working with the languages Matheson Whiteley had started to work with, but then just moving them slightly to one side, pushing them slightly to disrupt the decision whilst still acknowledging it. So all the details, such as the design choices and colour of the coat hooks or toilet brushes are considered. We came to the black luxury toilet paper dispensers, the beautiful nappy change, hand dryers and soap dispensers quite late on. We did a lot of research into bathroom fixtures and fittings as part of the process, and we became interested in these kinds of luxury objects and the sort of values that might be associated with them. So we decided we wanted that language to be in play in the artwork too.

Should we go back?

I chose a couple of readings in honour of THE INSTITUTE and I had imagined Joanne would read one and Tom would read the other. But I'm going to be Joanne, so I'm going to read Joanne's text.

About the end of the fifth year, Grandgousier, returning from the conquest of the Canarians, went, by the way, to see his sonne Gargantua. There was he filled with joy, as such a father might be at the sight of such a childe of his: and whilest he kissed and embrac’d him, he asked many childish questions of him about divers matters and drank very freely with him, and with his governesses, of whom, in great earnest, he asked, amongst other things, whether they had been careful to keep him clean and sweet? To this, Gargantua answered, that he had taken such a course for that himself, and that in all the countrey there was not to be found a cleanlier boy than he. How is that (said Grandgousier)? I have, answered Gargantua, by a long and curious experience, found out a means to wipe my bum, the most lordly, the most excellent and the most convenient that ever was seen.

What is that (said Grandgousier) how is it? I will tell you by and by (said Gargantua). Once I did wipe me with a gentlewomans velvet-mask and found it to be good; for the softnesse of the silk was very voluptuous and pleasant to my fundament. Another time with one of their Hoods, and in like manner that was comfortable. At another time with a lady's Neck-Kerchief. And after that I wiped me with some ear-pieces of hers made of Crimson sattin, but there was such a number of golden spangles in them (turdie round things, a pox take them), that they fetched away all the skin off my taile with a vengeance. Now I wish that Saint Anthonies fire burned the bumgut of the Goldsmith that made them, and of her that wore them: This hurt I cured by wiping myself with a Pages cap, garnished with a feather after the Suitsers fashion.

Afterwards, in dunging behind a bush, I found a March-cat, and with it I wiped my breech, but her clawes were so sharp that they scratched and exculcerated all my perinee; Of this I recovered the next morning thereafter, by wiping myself with my mother's gloves, of a most excellent perfume and the scent of Arabian Benin.

After that I wiped me with sage, with fennel, with anet, with marjoram, with roses, with gourd-leaves, with beets, with colewort, with leaves of the vine tree, with mallowes, wool-blade (which is a tail-scarlet), with latice, and with spinage leaves. All this did very great good to my leg. Then with Mercurie, with parsley, with nettles, with comfrey, but that gave me the bloody flux of Lumbardie, which I healed by wiping me with my braguette: Then I wiped my taile in the sheets, in the coverlet, in the curtains, with a cushion, with Arras hangings, with a green carpet, with a tablecloth, with a napkin, with a handkerchief, with a combing cloth, in all which I found more pleasure than do the mangy dogs when you rub them. Yea, but, (said Grandgousier) which torchecul didst thou finde to be the best? I was coming to it, (said Gargantua) and by and by shall you heare the tu autem, and know the whole mysterie and not of the matter: I wiped myself with hay, with straw, with thatch-rushes, with flax, with wooll, with paper, but,

who his foul taile with paper wipes,

shall at his bollocks leave some chips.

What (said Grandgousier), my little rogue, hast thou been at the pot, and that thou dost rime already ? Yes, yes, my lord the king, answered Gargantua, I can rhyme gallantly and rhyme till I become hoarse with Rheum…

Maybe Joanne's been practising too much and that's why she's not here. She's full of rheum.

Heark, what our Privy says to the Skyters:

Shithard

Squittard

Crackhard,

Turduous:

Thy bung

Hath flung

Some dung

On us!

Filthard

Cackhard

Stinkard

Saint Anthonies fire seize on

thy toane

If thy

Dirty

Dounby

Thou do not wipe ere

thou be gone.

Will you have more of it? Yes, yes, (answered Grandgousier).

I'm going to cease the reading there. It does go on for several pages, but that was where I was going to call it a halt and pass over to Tom.

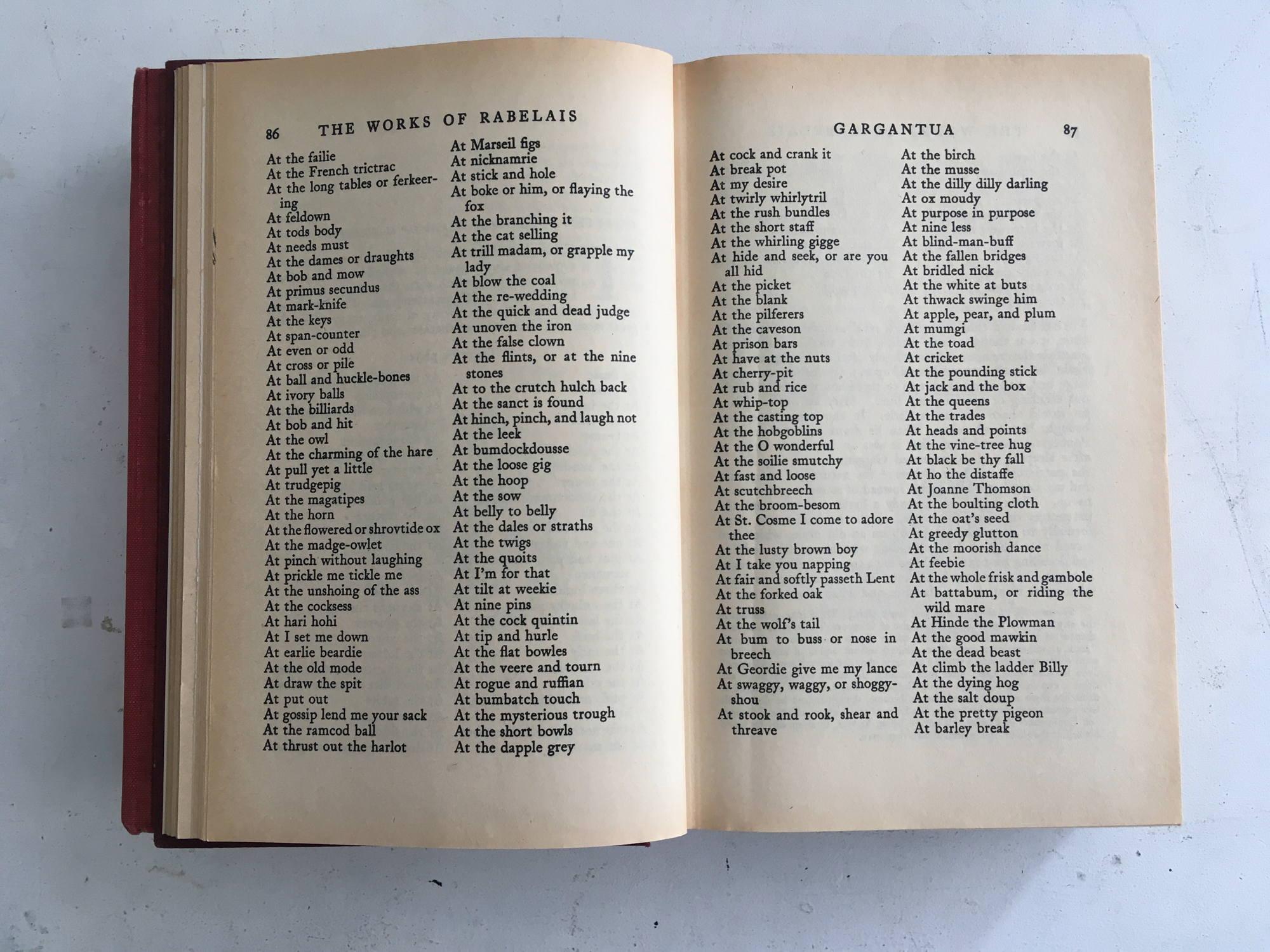

The Games of Gargantua.

Then, blockishly mumbling with a set on countenance in a piece of scurvy grace, he washed his hands in fresh wine, picked his teeth with the foot of a hog, and talked jovially with his attendants. Then the carpet being spread, they brought plenty of cards, many dice, with great store and abundance of checkers and cheese boards.

There he played

That's just a selection, it goes on and on.

Yeah

After he thus played well, revelled, past and spent his time, it was thought fit to drink a little, and that was eleven glassfuls the man. And immediately after making good cheer again, he stretch himself upon a fair bench, or a good large bed, and there sleep for two or three hours together, without thinking or speaking any hurt.

Thank you. Yeah, that was a great read, Tom.

Thank you.

So the readings are from Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel. I suppose my idea in choosing these readings was, on the one hand, topically related, but I suppose it's something in our collaboration that extends right back to that first research trip that I made with you and Joanne as part of the work you did with Studio Voltaire at Catterline. If you want to talk about that.

Well, the research trip was part of the first project we did with Studio Voltaire in 2005. We had made a sculptural work in the chapel there, but we also had the opportunity to do a kind of an extended research project. And what was particularly lovely about that project was getting to work with Fiona. And the other thing I was thinking about — and why it was interesting to be given this reading — is because in that event you set up a situation to bring Joanne and me into, and we were not entirely sure what it was, and then you allowed it to unfurl. It was a very generous thing to have that happen — for someone to set up a situation for you to enter, and because you trust them, something creative starts to happen. You booked us all into a cottage up in the Moray Firth up at Burghead and we went to the fire ritual...

And we did a lot of looking at recumbent stone circles around Aberdeenshire. It was a great shared imaginative experience.

Yeah, I think that setting up that situation or choosing a context for a very free-flowing research process to take place in, is, I suppose, an interpretation of your work in some sense. It's maybe… what I was trying to do at the time was pull things that I saw in your work out of it and relocate them in a way (speaking direct to audience). And actually when we were talking about the talk, I said to Tom and Joanne that we could arrange it in three sort of segments, if you like. So the first segment would be with these readings and then I had a bag of props — a bag of props that we could use to keep the conversation quite spontaneous and in the spirit of some of the collaborations we've done in the past. And for my first prop — there's nothing dodgy, don't worry — this actually relates back to Joanne and I. Joanne and I have maintained probably a closer relationship than (speaking direct to Tom) I have with you Tom, because Joanne and I use social media and message each other. We used to do a lot more a few years ago and I think we've probably just got bored of it and don't do it so much now.

But she did message me just when the announcement was made that the talk was going to happen. And what she messaged me was — she said, what are we going to wear? Right? And I did think if I was a bit braver, (pulling a tube dress from the bag) I would wear this. So this is my first prop and it's really... I have worn it, but that was pre-pandemic, and I'm not wearing it today. But I mean, it has…

Wow. That's beautiful.

I would call it my standing stone dress!

Where’s it from?

The internet. (Audience laughs) So that was my prompt to get you to talk about Burghead.

I love it. Incredible — some of the symbols on there — that circle is almost identical to a motif we use except ours has three lines across. How interesting. We haven't used that motif in these bathrooms, but it occurs in so much of our other work, that symbol moving across a surface.

It does remind me of your work, the scale of it, the pattern on that dress, the sort of outsize scale actually is probably more like the cat and boot work you did, the scale of the pattern. But I think maybe now when I'm looking at it (having watched loads of series of Only Connect on TV) I recognise that it's like one of the two readings we did. It's like that isn't it?

It makes me think back to that research trip and how much I enjoyed seeing those particular stone circles. The two upright stones, like two horns and the recumbent stone in-between. Massive structures and they're dotted all over Aberdeenshire. We had Julian Cope's book didn't we? The Modern Antiquarian. I guess there is something here in relation to meaning. These objects in the landscape — huge sculptural objects — and what do they have to do with you? You project meaning onto them and they kind of bounce it back at you and then you project it on again. You tell a story about it and it bounces back. Those recumbent stone circles really chimed with our practice and then they became a motif within the practice, something to use and position because of that very basic way they had a relationship to meaning making.

Yeah, I suppose it's about a presence that also refuses language in a way. Something about what you're saying about projecting meaning, but also the way that language and presence, and language as presence in your work, works together. I think that was maybe in that mix as well. Because the repetition in your work is something that, certainly for me… (grasping for sense) I totally see THE INSTITUTE FOR THE MAGICAL EFFECT OF ACTUALLY GIVING A SHIT as part of the continuum in your work. I think that although I can see how someone can experience your work without any prior knowledge of any of your other projects, with knowledge of your prior projects, the work is differently constituted. It's something that I think about quite a lot in terms of the commitment you make to an artist and how much time you're willing to spend with their work (as a viewer): how much more you will get out of specific artists' work if you do spend that time with it, return to it. And it is also about the sequence of experiencing the work. So THE INSTITUTE may be the first work that some people will — many people will — experience of your practice. The sequence of experience is important in creating the meaning.

We've always been interested in the potential for meaning-making and how an art practice can make meaning over a longer period of time, a period of space, rather than you just see a single work and that's it. A work can also be part of a much bigger project and the repetition allows for a kind of build up in this sense. It allows the practice to have a dialogue with itself, with the ways it makes meaning. If Joanne was here I think she’d agree that the practice could be understood as the artwork. One artwork that we add to and keep building up and editing and moving it on.

What you said about language is interesting. Actually, the first time I met you, was when I read a piece of your writing. When I read it, it struck me that it wasn't the normal kind of authorial voice coming out of your mouth — one taking for granted what you were saying and how you were saying it. The writing felt displaced and the language felt like it was possibly found and then positioned somewhere else and I really related to that. Then there was the text you produced after our research trip, The Pyramid, which was a constructed text. It was a text made up of other texts. It was constructed in the same way you might use materials — cultural materials — more overtly within an artwork. I very much related to that in terms of how Joanne and myself work with language. The language is often a positioned object to one side, over there, with an equivalent status to the other objects — like a tiled wall. We've always been suspicious of language when it enters art. We don't allow it to have authority or to claim all the meaning. We knock it into being just another component of the configuration that you bounce off against and the meaning occurs between these things.

You talked a bit before in the toilet about the seams of the wall, the bits where the four walls meet, as being deliberately awkward or deliberately misaligned in a way. And I wonder, thinking about a kind of authority or comfort within your own practice, how your commitment to form in a particular aesthetic allowed you to be confident enough to do that.

I guess it comes from working together over a long time, even though I now live in Newcastle and Joanne's down in London. We've been working together for 25 years, or maybe longer, and for a lot of that time it's more or less all we did, for good or for bad. So that's a lot of time to work, to develop a language. How did that language appear? Well, when I think back to the early days when we were beginning to work together, in some ways we could have been seen to be copying, or perhaps inhabiting, existing art practices. We were making pastiches in a way, but we were taking these different languages and making a new artwork out of them, and then positioning this somewhere else. So, one way to think about the aesthetic we've got now is as a sort of compression of that. The language has arisen through lots of those experiments and exercises and then slowly things that no longer function drop off, and the things that keep working, keep going, and this has slowly, cumulatively, built up to a kind of grammar — although it's always changing.

This is the last prop. There's only the books and two props. When I had mentioned that the conversation could proceed by way of prompts to Joanne, she said to me, 'Oh you're not bringing those shoes, are you?'. And I did. I was, but I said, you'll have to wait and find out. So she doesn't know that I did bring the shoes. And you will recognise them because we've used them as a prop in a different conversation on the Isle of Skye, where you made a different work.

That's right.

Do you want to describe that work, which probably moved on from The Pyramid? These are cool shoes. I've never worn them, obviously. They're too narrow for me. I did buy them to wear, but I've never worn them. Hence, they've entered the theatre of the conversation, shall we say. But I think the aesthetic is interesting in relation to your work. I kind of think of your work in this same kind of aesthetic penumbra. But I brought them to Skye as a prop to use, as a way to access… I don't know if you want to hold them, or put them on, they're only a size six!

Do I have to put them on and walk around?

Joanne actually did put them on when we did the talk in Skye, because they fit Joanne, but they don't fit either of us. But they were there as a way to begin a conversation about collaboration, you and Joanne collaborating, and that stemmed back to an essay Derrida wrote called 'The Truth in Painting', in which he describes the pairedness of shoes. You assume shoes are a pair and that if they're going to (be made to) walk, they have to be a pair. But he takes apart that presumption that anything presented as a pair is a pair. And in Skye, that's what I wanted to talk to you about, the pair of you as a collaborative team. But I think in this context it's slightly different. I think I thought about the shoes in relation to making the artwork walk if you like, because — maybe in contrast to the works you make for a gallery context — there is something different about the functional space that you've worked with here. It is interesting to think about how the artwork walks in that context, if you like, how — in some ways — it's more immediate.

Yes, there's something so interesting about making an artwork, which is also functional in a civic space. This is what's so great about doing the bathrooms. And I've really enjoyed the past few years because I've done a lot of work with Joanne out in civic spaces, public spaces. In these situations there’s an explicit context to work with and the artwork is out in the world... It has to survive in relation to everything around it, all the things that, within a gallery space, it is sort of protected from. We were interested in what it was to kind of test the languages we'd developed, out in the world. We wanted them to do something out there and not stay as a kind of privileged or protected language. It’s interesting to have an artwork that both functions practically in the world, but also has these other things we've been talking about — the possibilities of meaning-making. It's interesting to have those two things rubbing up against each other and that’s why, for me, the bathrooms are particularly exciting, it is a challenge to do it, but once you've done it, you feel like you only want to do that because everything else seems...

Less permanent?

Yes, or perhaps, like you said, doesn't walk. There is something about wanting your artwork to be active in the world. You want it to do something, to have legs and run around and do its business.

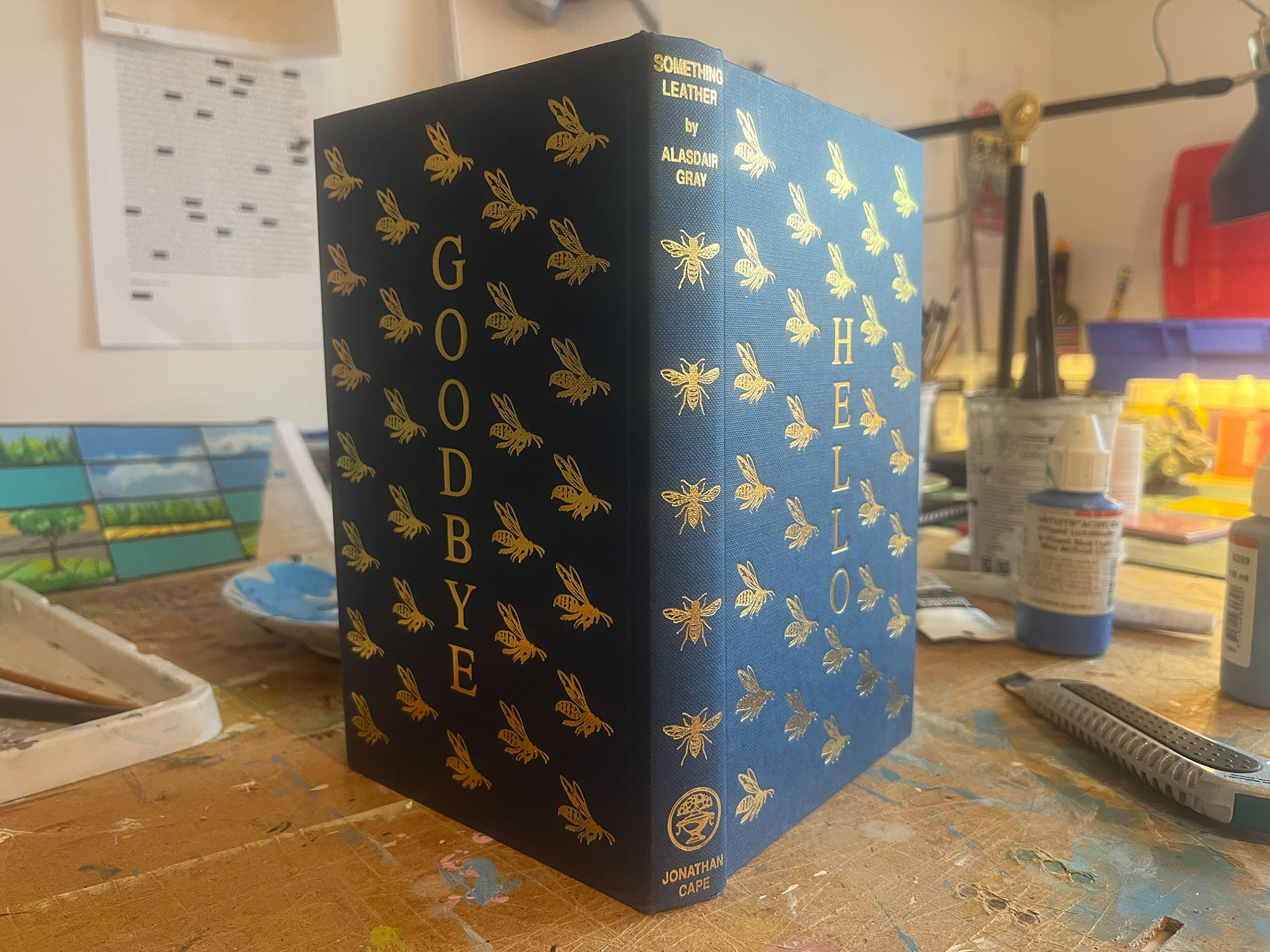

Yeah. I mean, when we were in the cafe earlier, you mentioned Fountain, Duchamp’s… can I call it a ‘classic’ classic artwork?... which I'd completely forgotten about. I literally haven't thought about it, I don't know, for years — and it was central to my PhD — but I have not thought about it for a long time. And it wasn't the artwork I thought about in relation to the artwork you've made here at all. In those terms, I was thinking about that idea of artworks existing in the world more ambiently, which I love I have to say, I love finding art in that way. I probably prefer it, actually, to the gallery experience. The sort of example I was thinking of wasn't Duchamp, it was Alasdair Gray's book covers. Now, I remember buying an Alasdair Gray novel purely for its cover and at the time I didn’t know it was an ‘Alasdair Gray’ book. Now I know who he is, I much prefer to encounter his work in that way, as book covers. I love encountering his work in a library or in a bookshop. When I've seen exhibitions of his work, what I like to see is the sketchbooks and the workings, the traces, the models, the things that he used as working documents. And so I was thinking about your artwork here in those terms.

And in a similar vein, today I went to the William Morris Museum in Walthamstow — it's really nice to experience Studio Voltaire after that, with the new garden outside which I know was commissioned at the same time as THE INSTITUTE FOR THE MAGICAL EFFECT OF ACTUALLY GIVING A SHIT, and to think about William Morris's ideas of art. I mean, I've never been to the William Morris Museum before and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I went to see the Althea McNeish textile exhibition. I didn't realise there were gardens there, beautiful gardens. Lovely roses — which Gargantua would wipe his bum on — and a beautiful herbal garden of all sorts of things to wipe your bum on. Jeremy Deller has been interviewed as part of the film that's on display. And I only watched it for about, I was going to say 10 seconds, but that sounds bad, about 30 seconds. (audience laughs) No, I watched it for a couple of minutes and he was talking about the didacticism of a lot of political art, and what he loved about William Morris was that he didn’t approach art in a didactic way, but was still making a political point through aesthetics. And I was thinking that that was a relevant context for your work here, but also for the garden outside that you come through into the refurbished gallery.

I love Anthea's garden. And you know, it is so interesting coming back and seeing how things are growing in the garden and then going and seeing our commission. Both artworks are now in the world, they're living things. And it's a bit like reading an Alasdair Gray book, you read it each night, you close it and see the cover, you put it to one side, you live with it. It’s also struck me how some of Anthea’s tiles are beginning to come into the café and I really like that. It feels like, oh, that artwork is really functioning, it's now creeping in and it's doing something in here as well. So what's happening to the toilets, then? Well, nothing's changed. Studio Voltaire haven't started putting colourful tiles in different places around the building. But I was thinking about the title. At the time when we did it, I thought this was a way of situating the wider experience as the artwork. But now, coming back, I feel it's much more, well, Studio Voltaire is probably THE INSTITUTE FOR THE MAGICAL EFFECT OF ACTUALLY GIVING A SHIT. So, the work has its own agency, it's breathing in its own way, and living in its own life. This is the thing about artworks, they're often more sophisticated than you might think. You don't quite know what they are, and they take time to reveal themselves. This is what interests me about this work, because it’s the first permanent artwork we've ever done. It’s going to be interesting to see what it becomes.

I think maybe it can sound quite trite saying, oh, London's most instagrammable toilet. It sounds like a throwaway remark, but actually, in terms of influence or, I suppose becoming part of people's lives, I think that's quite important in a way. That your work can travel through influence. You said just a minute ago that you and Joanne, when you started making art, you were copying other people's work. So, I suppose if you're positioned in a public site like instagram, you're entering that food chain — and maybe that even includes some of the motifs on my internet dress, I don't know! It's interesting to think about aesthetics and symbols and that nonverbal language, and how it relates to a moment. It's impossible to define the origin of that ongoing, shape-shifting moment and it is impossible to trace your influence or part in it in a linear fashion, but your visual language shows you to be part of that time: that kind of visual language is profligate and promiscuous.

That's it. That second bit of the title, A NOTE TO OUR FUTURE SELF, was a way to provoke that kind of thinking. To declare that this artwork has been made in time and is of its time. It happened to be me and Joanne who made it, but it's using the available languages, really, of this time. The title is an acknowledgement of this — let's not pretend we’ve generated it on our own — and also an acknowledgement that its meaning may change. It’s now six months since we finished it, but what will it mean in ten years, twenty years?

I think if Joanne had been here, I wanted to talk to her about our mutual enthusiasm for William Mitchell, who made poured concrete murals in the Sixties and Seventies. I say Joanne because I don't think this is a subject I've talked to you about ever, or maybe I have, but I just don't remember. Anyway, there are a few of his works being listed this week so I was going to talk to Joanne about that and the canonisation of William Mitchell today, because certainly I think he's not been taken that seriously as an artist until recently… I mean, he did the staircase, the Egyptian staircase in Harrods and I wonder if maybe some of the contexts that he worked in, and his particular background as an artist — the way that he became an artist and the kind of commissions he worked on, sponsored by concrete companies — meant that he was adjunct to the mainstream at the time. I don't know. Maybe the audience can also join in on that, because I'm not sure… I thought it was interesting this week that a couple of murals were listed, and I thought Joanne might extemporise.

Yeah, I think those models of practice which are between things, which spread out, which connect things, which are about existing spaces or working with them — they're undervalued. They're undervalued because there's a sort of fetishism for the individual, isn't there, and a fetishism for the singular artwork. Plonk and there it is, surviving on its own just there, forget what's come before it, what's to one side of it. Those civic practices of people like William Mitchell have certainly fed into this work. I mean, the work doesn't directly reference particular practices, but, if you like, they are poured into the pot — the tiles, the motifs, the figuration in a civic space — those sort of things. It is important for us that the work has a communality, that it is connecting, joyous and imaginative. That it has that function alongside the questions it provokes — what do you make of this? What did you expect this to be? What do you expect art to be? What are your values in relation to this? And so on.

It strikes me that it's part of Studio Voltaire's civic fabric as well, in that way. The design of the toilets and the garden too, she said, staring at Studio Voltaire staff (looking at Studio Voltaire staff)!

Yes, I'd be really interested to hear how you feel about it now or how it's fitting in...

JoeThere's a real element of pleasure. There's a real element of generosity. So we found in somewhere like with Anthea's garden, people really enjoy experiencing them. And I think there's an interesting contrast to, say, the kind of prescribed architecture of doing a capital build and the kind of weirdness... There's almost an invisible architecture here, that it's pared back, it's kind of classy.

Like very specific, like concrete floor, white walls...

JoeA certain kind of light which communicates a particular language and power. So it's really nice to have the toilets and the garden quietly asserting a challenge, I think, to those.

It's been interesting. They're also — I guess the work that I do at the gallery is predominantly exhibition-making, so working with you and Joanne and Anthea was the first time I'd done anything permanent, and having to sort of, like, slightly let go of the preciousness — yes, the soap dispensers might break, and that's the reality to it, and then you have to fix it . We talk a lot about the humour in the work and I would say, working with you and Joanne, it was incredible — like the rigour with how you consider everything is really incredible. And I think thinking about where the humour is in the work, for me, it's been almost less the big decorative faces or anything like that, it's been the experience of taking donors and the public around on tours and doing what we just did, and the kind of thing of like, please come into our toilet. And they're like… it’s a very strange kind of dynamics doing that with a group of people from the council.

I know we're just hitting about 8:15pm. Maybe we could take up your invitation to open up to the floor.

Oh, you didn't say what the font was for the mirror.

Farty Breath. When we found it we thought we can't use a font with a name like Farty Breath. But the thing is no other font did the job. That's the way it goes!

It's a perfect font.

PUBLIC 1I would like to ask something as someone who doesn't necessarily know your practice, but knows Joanne a little bit. I saw the work online before seeing it here, and now being here there's a sense, for me, of feeling I'm in a set. I feel like there's a play with scale. It makes me feel like I'm inside a set which I feel is supported by the title. I feel like I'm made to perform in some way but I’m not sure what I'm meant to be performing. And I wonder whether that's something that you carry through in the rest of your work?

Yes, it is and it's good to hear you had that experience. It develops from the practice of working with models in a particular way. Like I said, we walked through the whole situation as a maquette, so the viewer's experience is choreographed. Also I should say, it's not like we are in charge. There is a kind of theatre to the work, but it's not as if Joanne and me hold all the strings. We are making the set for us to walk into as well and we are not in a position of all-knowing. Gavin Wade coined the phrase 'a theatre of thinking' in relation to our work, which is kind of corny but I do like. I appreciate going into these kinds of situations myself, being led to see one thing and then something else and then perhaps you walk into another space.

PUBLIC 2I don't really have a question, but more of an observation. I made sure I came early enough to go and actually use the facilities, experiencing the work by going to the toilet. So what I thought was how rare it is to actually experience an artwork on your own because usually you're surrounded by crowds of people, everyone's in your peripheral vision. But actually it was really quite glorious and I realised that I had forgotten what that feels like to see a piece of work and experience it on your own.

Yes, you can go inside a cubicle and it's your space. You close the door and you lock it. When we first started thinking about how we would approach the commission, one of the things I had in mind was a story by M. John Harrison called A Young Man's Journey to Viriconium. It features a cafe in Huddersfield with a toilet downstairs. You would walk down the stairs and into the toilet and then through the mirror. You could climb through the mirror and access this other city, this magical city. So there was something for me about that surprise after opening the door, then closing it behind you and you're in this transformed space, which you alone experience, a space for your imagination. I'm really glad to hear it's got a bit of that spirit.

PUBLIC 2But then you're equally trapped whatever you do. You've got to see the work whether you want to look at it or not and no matter how long it takes you to do what you're doing. So it's a really interesting push and pull.

Yes — it might make you a little angry too.

PUBLIC 3I came across yours and Joanne's work years before I actually met Joanne. I think it was a platform like thing, something about the conditions of anxiety. And it stayed with me. And when I met Joanne, I immediately had this association with the work. So I think there's something striking about the particular language and use of space within your work that remains after having seen it.

I live next to the William Morris Gallery, and I was thinking about the space they have created in the garden, its design and planting. It’s interesting to consider this in a history of communist objects, how the art of William Morris, or the Bauhaus, wanted their languages and the aesthetic to be used by people. This is something the William Morris Gallery can teach people, that they can take away that message and those aesthetics.

You have been talking about how the work can exist within the world and take on its own life, and I believe this happens because of the language, because the particular aesthetic is very strong in the space — as for example, here, in Studio Voltaire. But I would almost want to see that extended. That visitors can kind of think, okay, how can I adopt and play with this attitude? How can I use this within my own life, not necessarily as decoration, but as a subversive tool. A kind of 'who gives a fuck'...

It's good to hear that. I like the idea that you can use an artwork in your everyday life to help yourself. Help in your thinking or for support and self-care. I really like what you said there about this artwork entering into your imaginative space because of its language. Because the language is, in a sense, a shared language. It has developed through the kinds of processes I mentioned Joanne and I were first involved in — working with the aesthetic languages available to us and the work developing as a kind of compression of this. So this is a shared language outside of ourselves. Someone mentioned to me the other day that another artist was making large pyramids, and wasn’t I pissed off that they’ve ripped me off? And I was like, uh?! I like it when this happens — the sense that these languages are circulating out there in the world.

I have the same experience with a lot of the art practices that I like, I carry them in my imagination. I carry particular works and they do help me. So I have always wanted our work to have this quality — for people to want to use it, or to take ownership of it, to feel they could get behind it or that it's on their side. Perhaps a commission in a civic space can make this more explicit.

PUBLIC 4I wanted to ask you about the work you make for domestic spaces. Because obviously you have the big works you have made but then also the much smaller domestic objects that have a relationship to the larger works. And also whether the bathrooms will become your 'Jim Lambie floor' that's going to look amazing in people's private houses? So my question is how this works for you? What is the relationship between producing public artwork and something for a private domestic space? Does it differ how you see the different aspects, or do you see your domestic things as being maquettes of your larger work?

Well, a good example of this is our ceramic editions, like the vases we have for sale in the shop through there. Working with a gallery like The Modern Institute opened up a situation that allowed us to think about what it is to produce things for this context: what kind of things could one produce for this? So it kind of grew out of that. Producing these ceramics allows for a process which is both very involved but also hands off. Our original maquettes come from a very hands-on activity of making and painting in the studio. These are passed on to James [Rigler] who produces the ceramic interpretation. There is obviously quite a bit of to and fro in this process, but ultimately the process allows for a certain distancing between the maquette and the ceramic. There is a remove from direct artistic mark-making and the ceramics are explicit about having gone through this process. We are interested in the sort of honesty this gives them as objects, in the sense they are desirable but also declare this process as to how they have been manufactured and editioned.

Someone did mention to me the other day, 'Oh, now you're going to get loads of commissions for bathrooms in private houses', but I just can't see that happening. I think the work is just too particular to where it is and it’s too awkward.

Are you up for commissioning bathrooms? Because I've got one that needs doing.

I'm more interested in a different situation coming along that we have to respond to. But, in a way, it’s the practice that leads us. Or the practice works with the situations it arrives into. We did some Swatch watches recently. I wouldn't necessarily have sought that out, but it was an opportunity to think about that situation and then produce an artwork with it.

I think it's amazing. Personally, I really enjoy that life that your work has. I love it. Seriously, there's one experience viewing art within a gallery context, and the pace at which it is experienced — I mean you (Public 2) were talking about getting the privilege to experience their work on your own for the length of time that you want to as well — so the pace you experience an artwork in a gallery is different to the pace that you experience as a book cover or illustration, and it's different again to the pace that you experience it in everyday life — in the way that Jeremy Deller was talking about William Morris not making didactic art. I feel that aesthetics — whatever that means — is for me a way of experiencing the world, not just in a gallery context, but through the things that you choose to furnish your life. And, I suppose, the things that you choose to represent you in your home, or what you're wearing, and all of that is non-didactic expression of personal aesthetics, which can have a political end, with a small p. I feel that actually there's a degree of non-didactic ‘training’, in a way, by putting things like the Swatch watch out into the world.

To get to the William Morris Gallery, I took the bus up to Walthamstow from Stratford and was going past the old-style London streets with little shops, corner shops, all the way right through Leyton. And it's all little shops, brightly coloured and stacked, with cafes and newsagents and little shops with plastic buckets outside them. Especially on the way up through Leyton, you've got the big corner pubs, very highly painted and decorated and some other buildings that have been painted more recently with patterns or different colours and some of them faded, then you've got graffiti, all sorts of things. And I just kind of feel that the aesthetics actually can — and I don't want to sound too preaching or evangelical — alert you to your own life in a way, to enjoying the daily experiences you have in life. Not in any big dramatic, critical way, but just that that kind of reverie is maybe training to ambiently experience the everyday, and that allows you to reconfigure what you think of as a journey through Leyton or wherever. I think that that, for me, is the power of objects that you put into people's daily lives. I think it happens in the gallery too, but it's a different type of attention that you pay to the artworks that you experience in a gallery. It is much more concentrated, intense and focused, and you maybe think about those objects in a different way, or they sort of work their way into your life at a different pace. Joanne sent me a Swatch watch for a ‘significant’ birthday after she asked me what I would like, and I told her, 'One of your Swatch watches, please!' And she sent me one and I love it. I'm surprised I haven't got it on — I should have worn it — but I think those objects are powerful, actually. They're not just things you buy in a shop — I mean they are things you buy in a shop, but that's not the limit of what they do or what any object does. So I think it's great. And if you get the chance to do more, you should do more Swatch watches.

The other place I visited in London today was the Museum of the Home, which is a lovely museum — and the thing I really loved about it were the domestic stories, or the stories about people's everyday lives through objects and through interiors. And I mean, it wasn't strictly preparation for this talk, but I think definitely bears a connection to it. And, yeah, they've got old Ikea catalogues and Habitat catalogues on display in the Museum of the Home and it is fascinating to see the changes and the different choices that we make around the way that we organise our life or how we build it.

Is there a final question?

PUBLIC 5I was thinking about how I first saw the bathrooms through Instagram and the kind of experience Instagram gives you. It’s like the Ikea catalogue. I think it’s a statistical fact that something like over 90% of the images or the surfaces are not real, they're just computer-generated profiles, and so you're looking at a false reality. Now having experienced the actual bathroom — generosity was the word that was used earlier — but it’s to do with sense or sensuality. Of course, the act of going for a crap is bodily and sensual in itself, but then there is the sensuality, the materiality and the depth of colour in the space in which you are sitting. Usually the last thing you want to do in a civic built toilet is to hang out there. You want to be in and out, but I just want to hang out in these toilets. Was this something that was discussed? How did that conversation go?

Yes, the particular materiality, and the sensuality implicit in this, was very much a part of our ethical concern in making the work. To make an experience that disrupts some of the assumptions we might have about such civic facilities, about how such toilets behave and how you feel as a body in those spaces. We talked a lot about that and the importance of an attention to detail in terms of the materiality.

PUBLIC 5You made an interesting point about the slippage in the way the walls are tiled. I’m the sort of person who is quite obsessed about such details so I always notice if the things like the tiling are wrong. But usually the tiling is wrong in a crappy way, like it’s all too perfect. But the slippage here feels to go beyond theatre. It’s the idea that it's not a grid. It should be a grid that locks you in, but that would be oppressive. So the slippage opens up the space.

That's good to hear. Much of this develops through quite intuitive ways of working between us, sharing and testing things. Why you might leave a system running and why it feels important not to close it down and make certain aesthetic decisions that in some ways might look better. It all comes down to the same kind of ethical trajectory of the practice that we have been talking about — what we want the artwork to do. We've got a shared vision about that. But I like what you said there, how the tiling emphasises the four walls like theatre flats, so that they could all kind of collapse, like a joke house.

PUBLIC 5Just one last observation, you have mentioned the quality, finish and the desirability of the materials, and I’m also thinking about the durability. It made me think about Richard Woods' fake cladding that he does. It's really quick and dead, it's fake and that's what he plays with. It's not necessarily something that is so highly finished so as to be durable. But is it important to you that the quality has that kind of professional durable finish, but at the same time it collapses?

Yes, I was thinking about this recently and came up with the phrase ‘meticulously re-inscribed’ as a way to think about the surfaces of many of our artworks. Usually this would be in relation to pattern and the painting, but it’s interesting how, with this project, it also encompasses the materials the surfaces are constructed from. It was important to have that kind of tension — an attention to details and materiality and yet the whole thing can fall down like a prop. It has to do with providing the kind of joyous experience in the space that I mentioned, a compulsion to be there and to look at the details, yet simultaneously the realisation it's a fabrication. It's not pretending that it’s not constructed. And, like Fiona said, if you start to become aware of that, then you start to look around and you realise everything is a construction. And when you start to think about that, you start to think, ‘Well, why is it like this, then?’